Augusto Odone surely was one of the best fathers of all time. Along with his wife, Michaela, Mr. Odone defied and then amazed the medical profession when he devised an apparent treatment for his son Lorenzo’s incurable neurological disease. The treatment was called “Lorenzo’s Oil.”

Mr. Odone died last week, but he left an indelible mark on the world of disease activism, setting a gold standard for what patients and their families might achieve with determination, good luck and the media. But Mr. Odone himself preferred to be remembered as a loving parent.

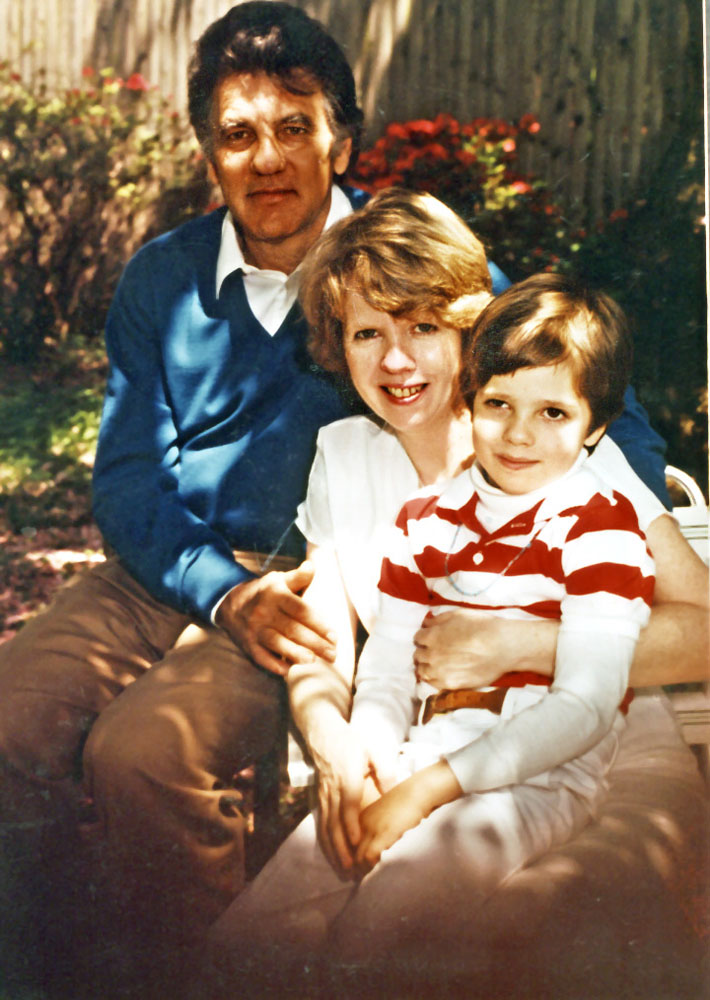

I had the opportunity to meet Mr. Odone — and Lorenzo — when researching a book on famous patients. He was an unlikely activist. An Italian-born economist working for the World Bank, Mr. Odone, Michaela and 5-year-old Lorenzo had moved from Africa to the suburbs of Washington in the summer of 1983. With his thick Italian accent and Old World charm, Augusto stood out among his neighbors. Michaela, who hailed from Yonkers, was an editor. Lorenzo, a precocious boy who spoke three languages, started kindergarten that fall.

Yet rather than thriving, Lorenzo experienced numerous problems, having temper tantrums, slurring his words and even falling on two occasions. Doctors initially suspected a difficult adjustment to a new country and school. But Lorenzo grew progressively sicker. When a neurologist finally made the diagnosis, in April 1984, the news was terrible: adrenoleukodystrophy, or ALD, a genetic disorder of young boys in which the myelin that protects the nerves of the brain and spinal cord becomes progressively damaged. Lorenzo, doctors said, would gradually lose his ability to see, hear, eat and walk. Death would soon follow.

The crestfallen Odones did what they could. They took Lorenzo to Baltimore to see the world’s top ALD specialist, Dr. Hugo Moser. Dr. Moser entered Lorenzo in a clinical trial of a special diet to try to lower the elevated level of very-long-chain fatty acids in the blood of affected boys. But it did not work.

It was here that the Odones went from ordinary to extraordinary parents. Refusing to believe that there was nothing else to be done, they became fixtures at the nearby library of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. Among the things the Odones discovered was that scientists across the globe who were working on ALD and other so-called demyelinating diseases had never actually attended a conference together. Not only did the Odones arrange this, in October 1984, but they began to study ALD themselves, asking probing questions of the scientists, generating hypotheses about the cause of the disease and beginning to develop possible therapies. When asked why he and Michaela did this, Mr. Odone, in typically modest fashion, said “We love this kid, and we don’t want to lose him.”

There have been other examples of this type of activism. Also in the mid-’80s, people with AIDS were becoming experts regarding their disease, advocating — often angrily — for increased research funding, faster approval of drugs and entrance into experimental protocols. Still, many physicians, as well as the parents of boys with ALD, resented what the Odones were doing.

Yet by 1986, the Odones had achieved the unthinkable. They had deduced that a mixture of two cooking oils, oleic acid and erucic acid, competitively inhibited the enzymes that overproduced the very-long-chain fatty acids that destroyed the myelin. They had begun to feed the oil to Lorenzo through the stomach tube he used for eating. By this time, Lorenzo was blind, mute, largely deaf and wheelchair bound.

In 1990, the Australian film director George Miller, best known for the “Mad Max” movies, contacted the Odones. He had heard their story and wanted to make a Hollywood film based on Lorenzo’s story. Released in 1992 and starring Nick Nolte as Augusto and Susan Sarandon as Michaela, “Lorenzo’s Oil” was an unabashed paean to the love and determination that the Odones had shown their son. One reviewer said it was “an inspirational drama that is truly inspiring.”

In my book, When Illness Goes Public, I discussed how many of the film’s scenes were inaccurate or misleading. For example, doctors had never tried to deny Lorenzo’s Oil to a segment of boys with ALD in order to conduct a randomized clinical trial. Nor had it been proven that the oil successfully treated the disease, as the film implied.

But these details were not the crucial aspects of Lorenzo’s story. What I witnessed when I visited the Odones in 2005 was quite remarkable. Michaela had died of cancer in 2001, but Lorenzo was alive at age 26, defying the gloomy prognosis the Odones had received two decades before. True, he did not interact with me and lay the entire time in a chair. But Augusto interacted with him frequently and believed that his son could understand him and still appreciated classical music and books. The most indelible image I have is of Augusto leaning down next to his grown son, quietly speaking with him and kissing him. Lorenzo died in 2008 at age 30.

And what about the oil? Did it really work? The current scientific consensus is that while it may prolong the lives of boys like Lorenzo, it does not really reverse the effects of ALD. However, astoundingly, it does prevent the onset of the disease in susceptible boys in at least two-thirds of cases.

Before the doctors could do so, Augusto Odone had guessed right. Hundreds of boys are alive and well today as a result.

Originally published in The New York Times (The Well blog), 30 October, 2013