In 1959, Jane Crile, the wife of Cleveland Clinic breast surgeon George (Barney) Crile, discovered a breast lump. Her husband was one a few renegade breast surgeons advocating that doctors no longer perform the disfiguring Halsted radical mastectomy but rather just remove the affected breast—which seemed to be equally effective.

When word of Jane’s mass got out to the surgical community, Crile’s colleagues were certain that he would recommend that his wife receive the standard radical operation. After all, it was one thing to rely on statistics when discussing breast cancer more broadly. But when it was one’s own wife, wasn’t it necessary to “do everything?”

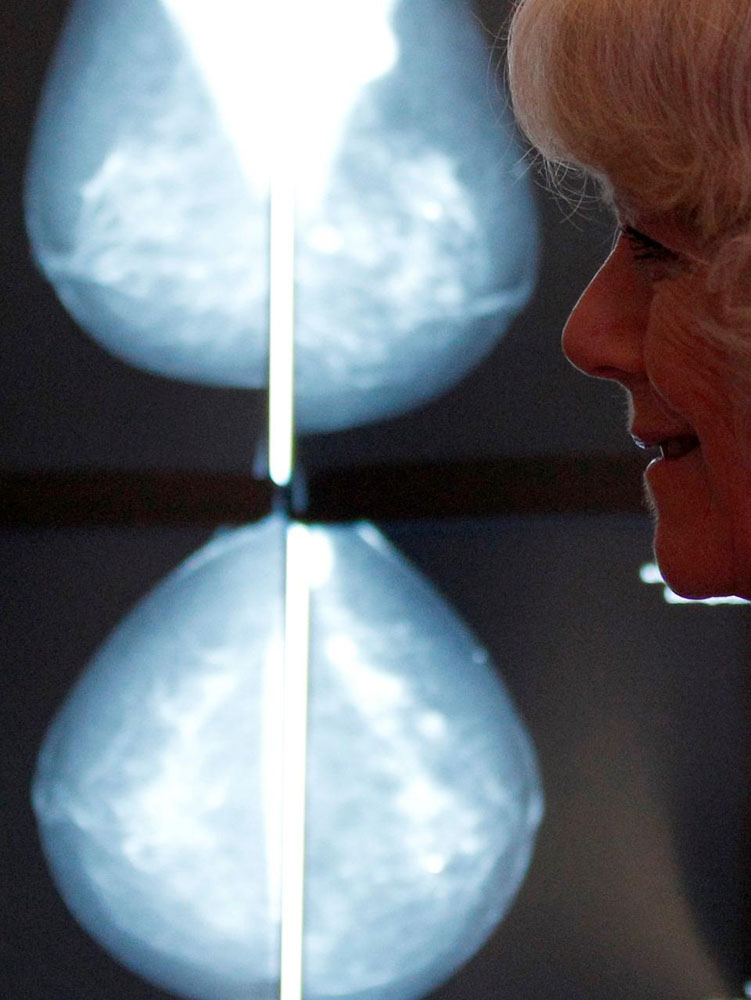

I recalled this story upon reading that the United States Preventive Services Task Force has just reasserted its earlier recommendation that women at average risk for breast cancer begin mammographic screening at age 50, not 40, as has been commonplace. It also advocated screening every other year, not every year. The task force did not advise against more frequent mammograms, but suggested that women and their physicians make joint decisions about how to proceed.

Even though multiple organizations have suggested cutting back on mammograms for many years, this news set off a predictable media frenzy.

On the one hand, advocates for the new regulations stressed the results of many randomized controlled trials, which they believe show little or no benefit for mammograms in women under 50. They point out that only one in 2,500 women screened annually in her forties will have her life saved due to mammography. At the same time, all such women will be exposed to radiation, which might be carcinogenic. Moreover, over 10% of screened women will have a false-positive result, which may result in extra testing or biopsies that turn out not to be cancerous.

On the other hand, advocates for screening—both physicians and patients—disagree. They argue that improvements in mammography make it a better test, thus invalidating the results of earlier clinical trials. Most importantly, they will tell stories of themselves or others who had a mammogram in their forties, discovered a cancer as a result, underwent treatment and are now in remission or cured. The message is clear: they might be dead if they had skipped having a supposedly “worthless” mammogram.

It is crucial not to minimize the importance of these stories. Breast cancer is a dreaded disease that raises not only issues of mortality but also femininity and motherhood. Breast cancer activism has been a great source of empowerment for women and has provided a model for other diseases.

At the same time, however, it is crucial to realize that having had a cancer detected by a screening mammogram and surviving the disease may have no connection at all. The randomized data showing minimal benefit for screening mammograms for women under 50 suggests that in younger women with dense breasts, the test is of limited value. Cancers that will ultimately kill are not cured by finding them earlier. Cancers that won’t kill are not influenced by when detection actually occurs, but rather by the available treatment.

Which brings us back to Jane Crile. When Barney Crile suggested that she just have her breast removed, and not the lymph nodes and chest wall muscles that would have created a huge hole on her chest wall and arm swelling, she agreed. Unfortunately, two years later she developed metastases in her lungs. She died about 18 months later of her disease.

Barney Crile’s critics used Jane’s story to criticize his then-radical beliefs about breast cancer surgery. Some even suggested Crile had killed his wife to try to make a point.

But that was inaccurate. Data that emerged in the coming decades showed that the amount of local surgery for breast cancer did not affect prognosis. Rather, it was whether the cancer had already invisibly spread at the time of diagnosis. Jane Crile’s cancer had, which is why, in an era before chemotherapy, she died.

As of now, it seems unlikely that insurers will stop funding screening mammography. It is politically too dicey. So women who desire mammograms should continue to be able to get them. But let’s try to respect the data that scientists have generated about the test, and the efforts of groups like the task force to create honest and useful recommendations. Stories like that of Jane Crile and other women with breast cancer are undoubtedly moving, but they may not tell the whole story.

Originally published on forbes.com on January 12, 2016.