When Dr. Nicholas Gonzalez died in July, there was not much notice. He did not get an obituary in The New York Times or in most other major media outlets.

Yet Dr. Gonzalez, whom I interviewed in 2003, was a fascinating figure in the world of cancer, walking a tenuous boundary between orthodox oncology and alternative medicine — or what is now called complementary medicine. Though his beliefs and treatments have fierce critics, his insights shed light on the mysteries of cancer.

Beginning in 1980 as a medical student, Dr. Gonzalez reviewed more than 1,000 medical charts from a dentist named William Kelley. Dr. Kelley claimed to have cured his own liver and pancreatic cancer in the 1960s by rejecting surgery, radiation and chemotherapy in favor of nutritional therapy, consisting of pancreatic enzymes, minerals, vitamins and coffee enemas.

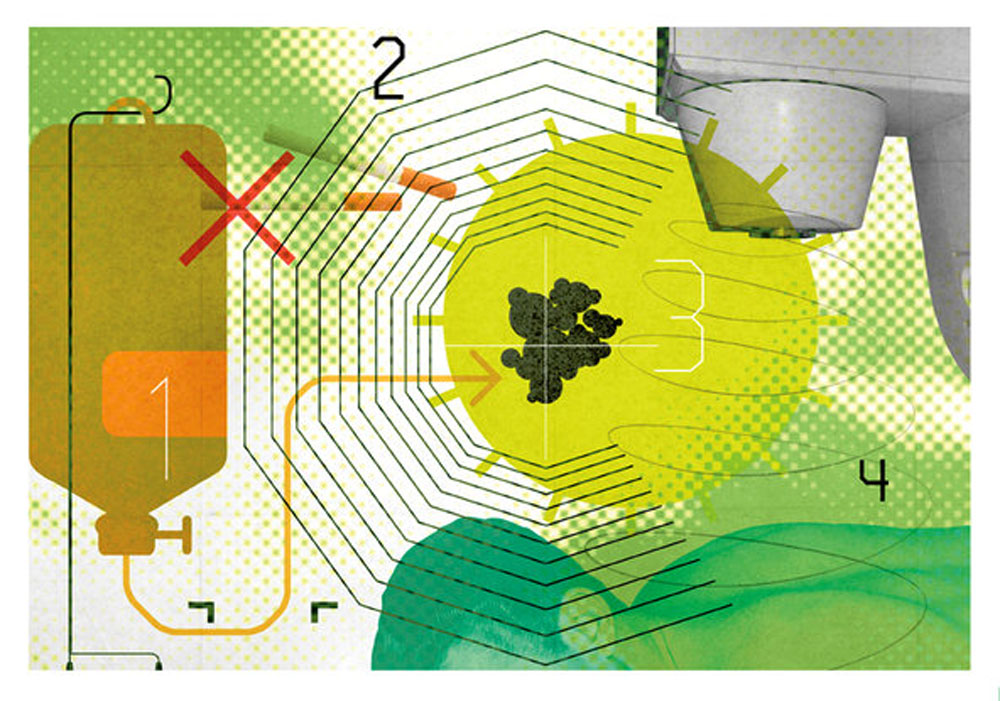

The pancreatic enzymes were critical because, Dr. Kelley believed, they digested cancer cells. But his treatment relied on two other theories. First, he claimed that the regimen also detoxified the body, allowing patients’ immune systems to destroy cancer. Second, he believed that all cancers differed from patient to patient, so each patient should receive individualized treatment.

Once Dr. Kelley — working with a group of like-minded physicians — began treating patients, he ran afoul of the American Cancer Society (who claimed he was a quack) and various professional societies. Eventually, his dental license was suspended; patients interested in his regimen had to travel to Mexico to be treated by him.

After Dr. Gonzalez finished his chart review and interviewed more than 400 of Dr. Kelley’s patients, he concluded that the regimen worked. Hundreds of people who supposedly had terminal metastatic cancer had lived for five, 10 or more years.

Dr. Gonzalez later completed a fellowship in immunology and began practicing in New York City, treating a wide range of ailments, including chronic fatigue and multiple sclerosis. But it was the treatment of cancer — especially end-stage cancer — that brought him both fame and controversy.

Working with another physician, Dr. Linda Isaacs, who at one point was his wife, Dr. Gonzalez advocated a nutritional regimen similar to that of Dr. Kelley, including vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. He prescribed coffee enemas, which Dr. Gonzalez believed improved liver function and the excretion of waste. Finally, he gave cancer patients up to 45 grams of pancreatic enzymes. According to Dr. Gonzalez’s website, his cancer patients took 130 to 175 capsules daily, and his noncancer patients took 80 to 100 each day.

In 1994, Dr. Gonzalez conducted a pilot study of his program for 11 patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. Five lived longer than two years, and two lived longer than four years. No patients in a comparison group treated with standard chemotherapy survived more than 19 months. This led the National Institutes of Health to fund a controlled trial at Columbia University that formally compared Dr. Gonzalez’s regimen with chemotherapy for 55 patients who had advanced pancreatic cancer. The results, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2010, showed that on average, the patients getting the chemotherapy lived three times as long than those getting the enzymes.

I interviewed Dr. Gonzalez while researching a book on famous patients, which included the story of the actor Steve McQueen, who traveled to Mexico in 1980 to try Dr. Kelley’s regimen for his terminal mesothelioma. (Mr. McQueen ultimately died of his disease.) If I arrived expecting to find a shady character who manipulated vulnerable patients, I did not find one. Dr. Gonzalez was highly affable and professional. He assured me that he never recommended his treatment over cancer therapies with proven value. He was available, he said, for those with progressive disease or those who rejected standard chemotherapy.

But more affecting than Dr. Gonzalez were his patients. He introduced me to one woman who had been diagnosed with metastatic ovarian cancer more than 10 years earlier but was alive and well on his protocol. To underscore his point, Dr. Gonzalez showed me her pathology report, which confirmed what he had said. I met several other patients whose lives, they believed, had been saved by the hundreds of capsules they ingested each day.

This sentiment is reflected in dozens of online comments recorded after Dr. Gonzalez died unexpectedly at age 67 on July 21. Jen H. from Washington wrote: “The hope he provided to his patients when all hope had been removed was and is invaluable.” Another person wrote that Dr. Gonzalez had sent him a hand-written note explaining why he would not be able to treat the writer’s dying father.

As someone trained to practice scientific medicine, I found my encounter with Dr. Gonzalez to be a challenge. Not only was there no good data showing his regimen to be effective, but much of what he prescribed did not really make medical sense. Wasn’t it more likely that most of his patients had been misdiagnosed or that their cancers had stopped growing for other reasons? Dr. John Chabot, the Columbia professor who ran the N.I.H. trial, admired Dr. Gonzalez’s devotion to his patients but felt he was “misguided due to his zealotry.” Also, because insurance companies rarely pay for unconventional treatments, Dr. Gonzalez’s regimen often cost his patients tens of thousands of dollars.

Still, shortly after my visit with Dr. Gonzalez, when an acquaintance was dying of cancer and had exhausted all treatment options, I gingerly mentioned his work and the supposedly cured patients I had met in his office. She was not receptive. She told me that she would never try anything so unscientific, no matter how desperate she was.

Despite the lack of evidence of the treatment’s efficacy, Dr. Isaacs continues to use the Gonzalez protocol for patients who see a connection between cancer and nutrition. And Dr. Gonzalez’s work lives on in other ways. New immunotherapy treatments seek to harness the body’s immune system to fight cancer. And recent studies suggest that cancer is a different disease in different people and that treatments need to be personalized.

Originally published on the “Well” blog of the New York Times on January 14, 2016.