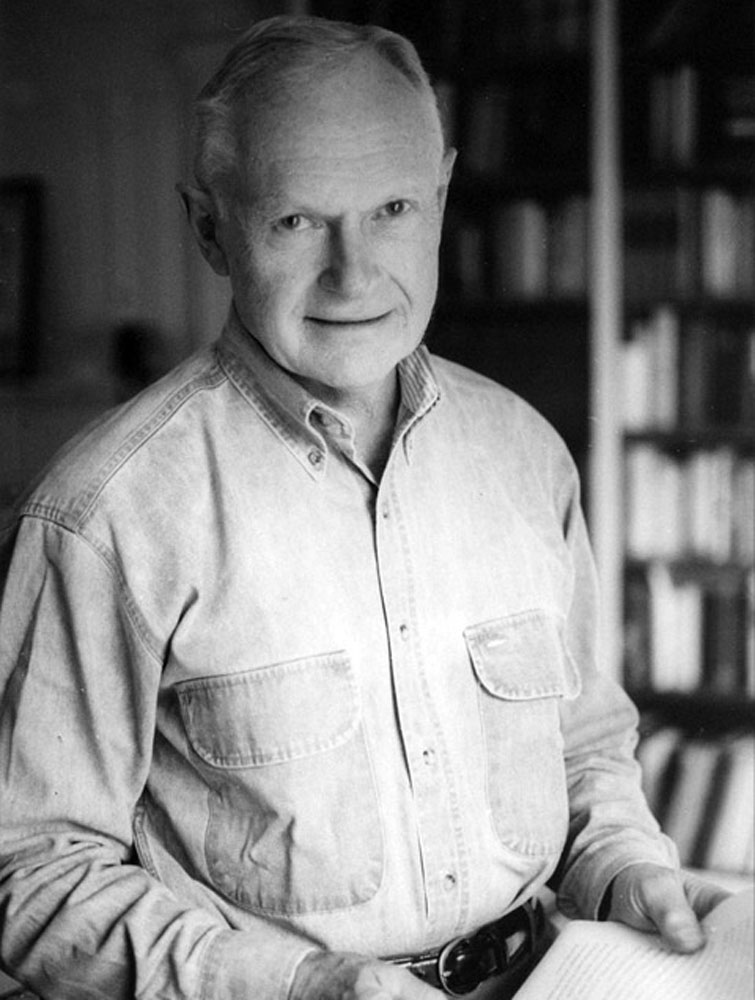

Most of the obituaries for the physician-historian, Sherwin A. Nuland, who died on Monday, March 3, have rightfully emphasized his 1994 book, How We Die, which won the National Book Award.

But Nuland held an interesting place in the world of the history of medicine, a torch holder for an older type of scholarship that praised great doctors of the past. Maligned at times for what he himself called a “gee whiz” approach to his craft, Nuland’s brand of history — and its celebration of a march of progress in medicine — still holds an important place both within academia and among the general public.

The earliest historians of medicine were, in fact, physicians. Many of them wrote biographies of their mentors or other past doctors, who they believed had made important contributions to medicine. But physicians also prized medical history because they believed that it conveyed important aspects of humanism to medical students who were entering the profession. The stories of earlier physicians, it was believed, taught professionalism and counteracted deleterious trends in medicine, such as an overreliance on technology and specialization.

Nuland fit easily in this mold. He began his career as a surgeon, but in the 1980s began to write history. His 1988 book, Doctors: The Biography of Medicine, was perhaps his most explicit love letter to doctor-driven history. The book is a series of chapters detailing the stories of great doctors, beginning with the father of modern medicine, the ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates.

Subsequent chapters of the book told the stories of individuals, such as the 17th century English physician William Harvey, who discovered that blood circulated within the body, Rene Laennac, the 19th century French physician who invented the stethoscope, Ignaz Semmelweis, the 19th century Hungarian obstetrician who realized that doctors were causing deadly childbed fever by spreading it from autopsy specimens to healthy patients and William S. Halsted, the pioneering Johns Hopkins surgeon at the turn of the 20th century who popularized the radical mastectomy to treat breast cancer. Nuland included one famous woman: Helen Taussig, one of the team that developed a heart operation that saved the lives of “blue babies” whose blood did not contain enough oxygen.

By the time Doctors came out, Nuland was cutting against the grain of historical scholarship. The new “social history,” which emphasized the lives of ordinary individuals, such as patients, was in ascendance. Patients whose experiences were negatively affected by their race, gender or class attracted special attention. Nuland’s type of work, with its hagiographic approach to doctors, had become “bad” history.

Nuland was well aware of this dynamic. At the meetings of the American Association for the History of Medicine, which he and I attended regularly, there was an annual breakfast at which the group’s “clinician-historians” endlessly debated whether or not their work had become obsolete. The introduction to Doctors is full of self-deprecating asides about how some of his colleagues found there to be a “defect” in his scholarship. “But I do not apologize,” Nuland wrote. “I am most assuredly not only impressed but quite frankly flabbergasted at the talents, industriousness and accomplishments of most of these people,” (1).

Even if Nuland’s peers sometimes took him to task, his books did better than most. How We Die, for example, sold over 500,000 copies. He also wrote a well-received memoir, Lost in America, that told the story of his immigrant family and his decision to enter medicine.

And although Nuland was criticized for overlooking the flaws of his physician-ancestors, he was well aware of how mistakes were made on the road to progress. When I interviewed him for my 2001 book, The Breast Cancer Wars, he admitted that he and his fellow surgeons were so enamored of Halsted’s radical mastectomy that they bullied their patients into having the operation even after its value had been questioned. His 2003 book on Semmelweis criticized the famous physician for being so stubborn that his insights into the contagiousness of disease were rejected.

Ultimately, it was Nuland’s own humanity that made his writing so compelling. Quoting the legendary Johns Hopkins physician William Osler, Nuland wrote that physicians should study history not only to learn about past events, but to study “the silent influence of character on character.” [2]

I was reminded of the influence of character when Nuland recently sent me an e-mail apologizing that due, to his illness, he would not be able to do an advance reading of my new book, “The Good Doctor.”

“I believe a book like yours should have a wide readership not only because of its contents, but also the literary skill of its author,” he kindly wrote. “May it have the success it deserves.”

Two days later, he died.

Originally published in the Huffington Post, March 7, 2014