We owe the “rounders” an apology. Rounders were tuberculosis patients in the early 20th century who left hospitals against medical advice when they felt better and later wound up at another hospital. While “making the rounds,” they potentially infected others with their disease. Health officials routinely criticized these individuals for endangering the public.

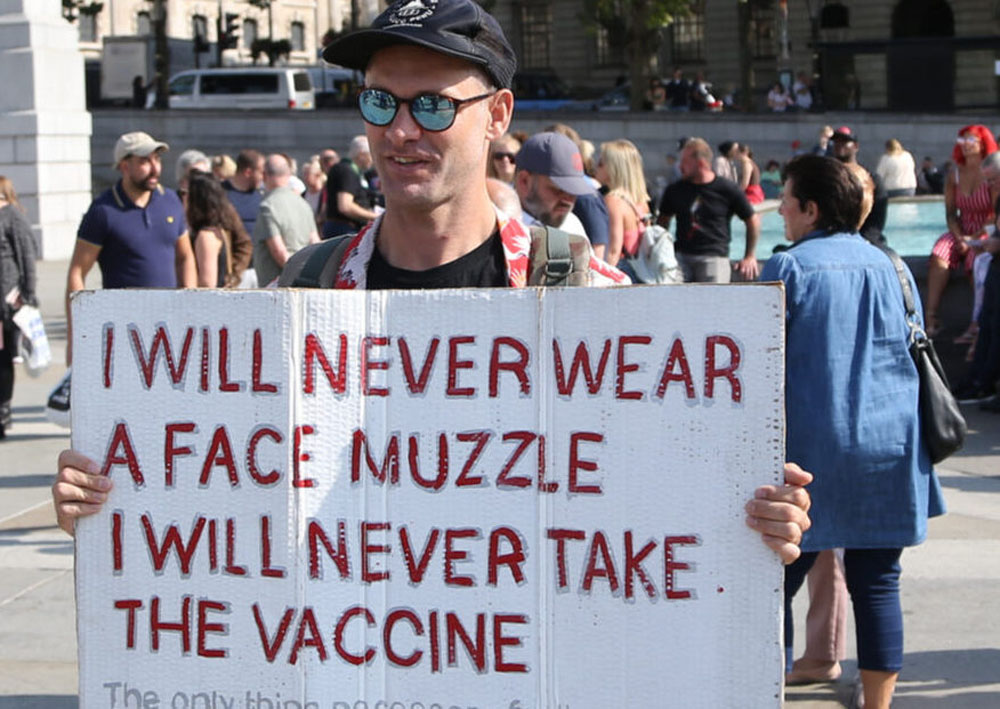

One of the most surprising aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic for those of us who teach the history of public health is how unwilling many Americans have been to adopt health measures to protect others. Over the Thanksgiving holiday, tens of millions of Americans traveled, despite the fact that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged them to stay home and the overall death rate from the coronavirus is approaching 300,000. Should recent events make us revisit aspects of the history of public health? And how can these stories inform future public health efforts during pandemics?

Tuberculosis was the disease that most forcefully established the right of public health officials to control the behaviors of infectious patients. Building on the recent discovery by German scientist Robert Koch that tuberculosis was a communicable disease, Hermann Biggs of the New York City Department of Health established a groundbreaking program in the 1890s to fight the spread of the disease—opening public health laboratories, tracing contacts of patients and quarantining the actively ill.

There was substantial early pushback in New York and elsewhere, but ultimately public health science won the day. The right to mandate specific behaviors became legally codified in 1905, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that officials could require the payment of a fine to the health department from citizens who refused to be vaccinated for smallpox. “There are manifold restraints,” the court wrote, “to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good.” Two years earlier, New York City had opened Riverside Sanatorium to forcibly detain tuberculosis patients on an island in the East River.

Early health officials had nothing but contempt for rounders. Referring to an earlier term for tuberculosis, “consumption,” Biggs wrote that “homeless, friendless, dependent, dissipated and vicious consumptives are those which are likely to be most dangerous to the community.” The disdain for rounders occurred not only because of their behavior, but also because they were often poor, unemployed and immigrants.

Keeping infectious tuberculosis patients hospitalized for long periods was made especially difficult because no effective treatments for tuberculosis existed at this time. As the disease could last for years, it was hard to justify—and pay for—essentially permanent hospitalization.

But by the 1950s, effective antimicrobials existed that could treat the disease if taken regularly for 12 or more months. Once again, however, patients who felt better insisted on leaving their sanatoriums and became noncompliant with medications. Erratic medication use bred drug-resistant, potentially untreatable strains of the disease.

This lost opportunity to cure tuberculosis patients led to a rejuvenation of aggressive public health measures. Seattle, for example, wound up detaining thousands of individuals against their will up until 1973. Health officials there no longer used Biggs’ overtly pejorative language, but routinely termed their “recalcitrant” patients to be “menaces to the public’s health.”

Once again, those detained at Seattle’s Firland Sanatorium came from the poorest populations in the city—mostly itinerant, alcoholic white men who lived in flophouses along the city’s Skid Road. At times, officials also detained Native Americans and women. A Firland chart referred to one patient as “this wild young Indian girl.”

One might argue that tuberculosis and the coronavirus are apples and oranges. After all, people with tuberculosis had an actual disease while those recently traveling probably believed themselves to be healthy. But, in fact, a major reason that some tuberculosis patients demanded their liberty was that they felt fine and, indeed, were no longer actively infectious. The doctors had merely decided that unreliable Skid Road patients needed to stay hospitalized and take their pills until they were permanently cured—which often took months after they were no longer infectious. “We want to know by what right, and on what authority, this is being done,” complained one patient.

Historians writing about the detention of patients with tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, such as typhoid fever patient Mary Mallon (“Typhoid Mary”), have been highly critical of these episodes, viewing health officials as overly aggressive—as well as racist and classist. Patients, according to this paradigm, justifiably rebelled because they were being singled out unfairly.

But what if the explanation is simpler: despite the dangers presented by serious infectious diseases, many people—regardless of their social class—don’t like restrictions, whether for their own good or the good of others. Two other facts support this conclusion. First, the U.S. has always had a strong tradition of individualism and libertarianism. And second, nonadherence to medical recommendations is extremely common, regardless of patients’ health insurance or medical literacy.

If true, perhaps we need to revisit how we have understood the history of restrictive public health measures. Maybe it is not merely a story of disadvantaged populations rejecting well-meaning but insensitive interventions imposed by the state, but rather a more universal rejection of being told what to do. Perhaps widespread repudiation of public health authority has been going on all along—but historians (aside from those writing about vaccination) have largely told the stories of those whose forcible confinement engendered controversy.

What might this conclusion mean for future public health measures? Even though Jacobson v. Massachusetts theoretically provides the legal framework for restrictive measures during a pandemic, it does not ensure that citizens will comply. And it is hard to imagine health departments having the resources or political will to forcibly change people’s behaviors.

We must double down on our efforts to engender a communitarian mindset, even in a country that cherishes its individual liberties. One way to do so is to depoliticize public health, emphasizing what the science does and does not show. In addition, let’s focus less on whether people are breaking the rules and more on mitigating bad outcomes when they do so. For example, those who travel can be encouraged to reduce contacts and adopt other safety measures.

It is tempting to tell the history of public health as a story of right versus wrong. And egregious violations of public health need to be condemned. But it makes sense to acknowledge our longstanding, complicated responses to epidemic diseases.

Originally published on thehastingscenter.org on December 2nd, 2020.