When it came to offering medical interventions to severely ill patients with no hope of recovery, my father had a fiercely strong opinion: They were inappropriate. For decades as an infectious diseases specialist, he had been asked to treat infections in dying patients. Whenever possible, he said no.

But when I approached my dad, who had developed end-stage Parkinson’s disease, to ask what his end-of-life wishes were, he indicated a desire for aggressive measures.

Bioethicists have long debated the issue of “precommitment.” Which wishes are more valid — ones that someone indicates in advance or those expressed during serious illness? My father’s case provided a vivid case study of this issue.

A main reason that my father had entered the field of infectious diseases in the 1960s was medicine’s new ability to treat severe infections. What was then the fairly recent discovery of antimicrobial agents like penicillin and streptomycin meant that endocarditis, tuberculosis and other previously untreatable infections could now be cured.

But as my dad’s career progressed, his consults were as often as not on gravely ill patients who had experienced infection after infection and were getting worse, not better, even if a particular infection could be treated. Typically, these patients lived in nursing homes. Many had dementia. Some required permanent feeding and breathing tubes. Others had terminal cancer. One of his consults, I learned through reading his journals, had an “absolutely rampaging lymphoma” and was “obviously terminal and slipping rapidly,” but her primary doctor wanted to treat yet another infection.

My father knew that infections were often the final straw in the deterioration of so many of the body’s vital organs and functions. In other words, infections were what helped terminally ill patients die. To perpetually treat infections in such cases, he often said, was “inhuman and morally wrong” as well as “professionally bankrupt.” My dad tried, whenever possible, to encourage patients, family members and his physician colleagues to reconsider the reflexive tendency to treat.

Unfortunately, my father was given a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in 2001 at age 69. By 2006, he was having tremendous difficulty moving and had stopped working. Over the next several years, his mental status also worsened. He was profoundly lethargic, unable to carry out complex or detailed conversations. But there were also moments of lucidity.

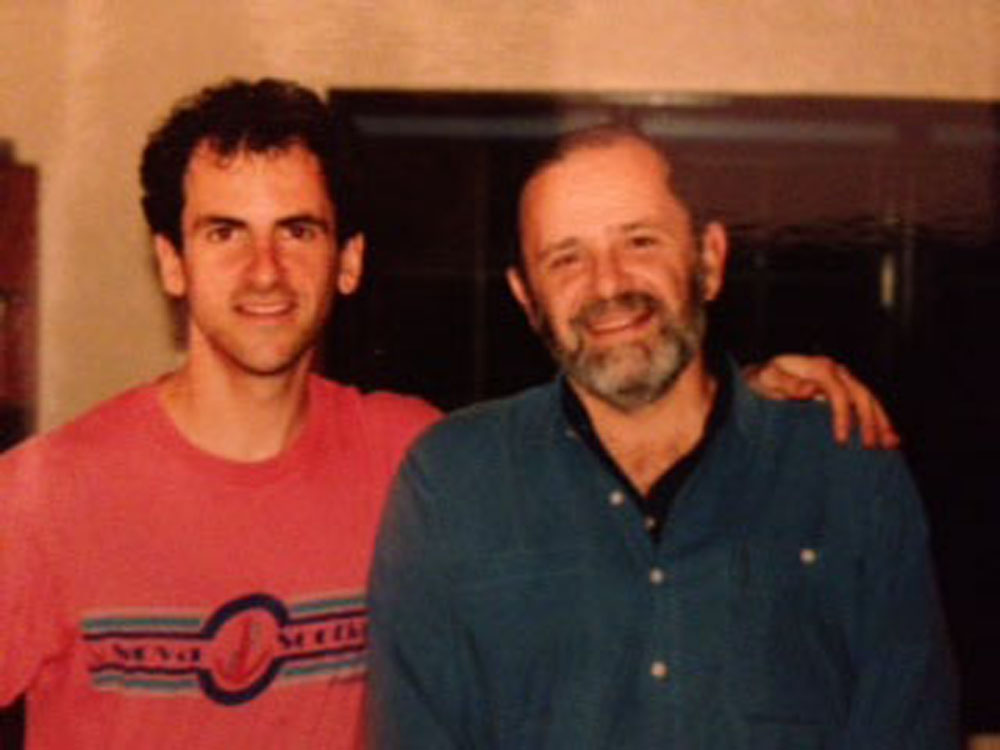

Finally, in November 2011, my mother had no choice but to admit him to a nursing home. I will never forget when I first saw him there. He was sitting in a wheelchair with his head almost on his lap. He was completely dependent on others. This image of my dad was particularly poignant: The last time I had been in a nursing home with him was when he was the medical director of one, caring for the same type of sad souls he had now become.

The time had come to clarify what types of interventions my father wanted. I knew what I hoped to hear. Not only did I know his opinions about inappropriate treatment, but he had written some notes when he began to seriously deteriorate. He said that he was “taking steps to ease my passage.” Some with his condition, he added, “have taken drugs.” Regarding his wife — my mother — he wrote that she “doesn’t deserve to struggle with me anymore.”

But when I asked what he wanted, these notions had disappeared. He said he would be willing to go to the hospital if he got sicker and even go on a ventilator. “Sometimes they can really help,” he said.

I tried a different tack. “Are you content,” I asked, “living in a nursing home, being confined to a wheelchair and sleeping most of the time?”

The man who had dreaded ever winding up this way answered, “Yes.”

My father’s change of mind was hardly unprecedented. With the rise of living wills and health care proxies, people now often indicate how they want to limit medical interventions if they reach a state of irreversible infirmity. Although such documents are intended to take effect when serious illness clouds judgment, bioethicists such as the Washington University professor Rebecca Dresser have compellingly written that people’s goals may genuinely change when they confront a lessened quality of life and their potential death. As a result, she argues, a patient’s “experiential interests” at this later time should take precedence over the earlier wishes.

In my father’s case, however, I simply could not throw his previously stated wishes out the window. Ultimately, my mother, sister and I concluded that it was impossible to advocate such specific choices so fervently in one’s lifetime without their being a part of one’s permanent makeup — even if they could no longer be articulated. I realized that other families, in similar situations, might choose the opposite strategy.

We did not tell my father we were overruling him but rather quietly put him into the nursing home’s hospice program in early 2012. Many months later, he caught an infection — one that was probably treatable. Instead, the staff gave him morphine to ease his discomfort. Within 24 hours, he had died.

Originally published in the Opinionator section of the New York Times on April 8, 2015