It is not hard to be moved by Richard Martinez’s emotional public calls for gun control in the wake of his son Christopher’s death during the recent shootings in Santa Barbara. But they hold special resonance for me and my family. In January of this year, my 9-year-old nephew Cooper Stock was killed by a reckless driver in New York City. Like Martinez, Cooper’s mother, my sister Dana, has become a vocal public health advocate — in her case, for traffic reform.

I also know about these topics in another way. As a historian of medicine and public health, I have written for years on past efforts to balance the public’s right to safety with the individual rights of American citizens. But experiencing a public health tragedy at such a personal level has forced me to rethink some basic premises about what a society considers acceptable harm.

Since the 1970s, social historians have been highly critical of many public health campaigns. For example, they have documented how health officials in San Francisco unfairly quarantined Chinese residents of San Francisco during an outbreak of the plague in 1900 and how more than 30,000 prostitutes with venereal diseases were incarcerated during World War I.

And, of course, there was the Tuskegee scandal, in which the United States Public Health Service, under the guise of studying the natural history of syphilis, deliberately left poor African-American men with the disease untreated between 1932 and 1972.

My own research has revealed similar examples. At Seattle’s Firland Sanatorium between 1947 and 1973, doctors used the institution’s locked ward — set up to detain actively infectious tuberculosis patients who were public health threats — to maintain order. Doctors locked up noninfectious patients for weeks or months as they saw fit. Amazingly, when the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union visited to investigate patients’ complaints, it dropped the issue.

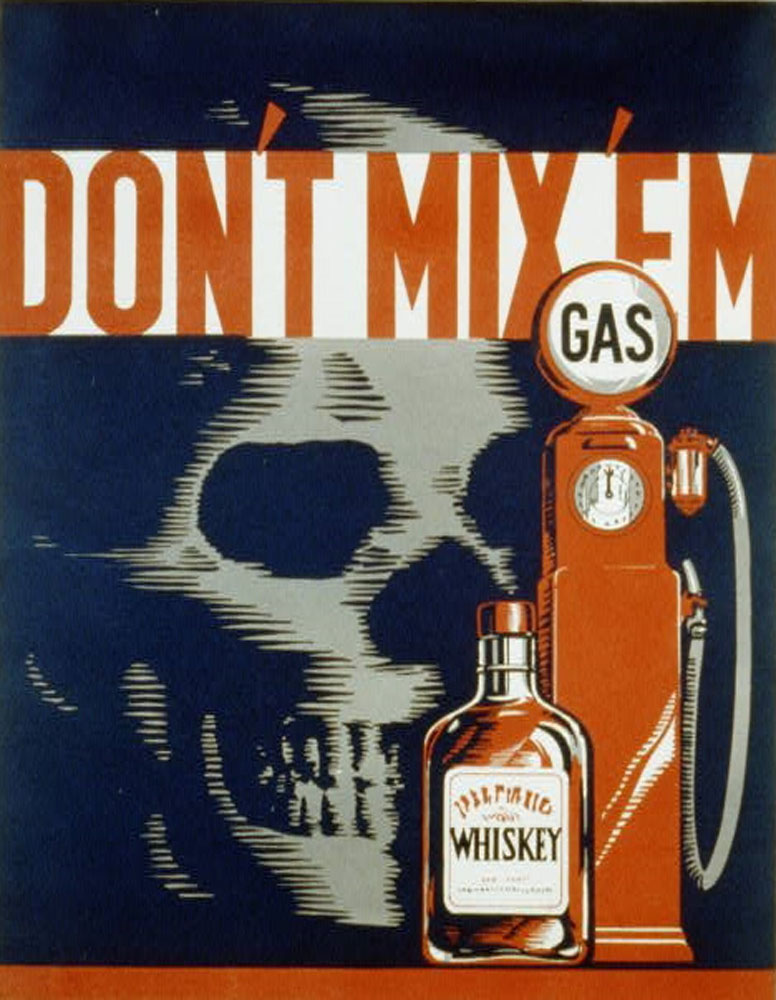

These and other stories about the excesses of the public health establishment have helped to foster a libertarian streak that has always existed in the United States. Thus, there has been opposition to even seemingly reasonable public health campaigns — such as mandating seat belts, tightening drunk driving laws and eliminating smoking from airplanes and restaurants. Still, I have always appreciated constructive opposition to what has been termed a “nanny state.”

Of course, the battle between public safety and individual rights has been particularly heated in the area of gun control. The National Rifle Association and other opponents of strict gun laws use familiar libertarian arguments about the right to bear arms — in this case codified in the Second Amendment. Despite several recent high-profile shootings involving mentally ill individuals who were able to obtain guns, most notably the 2012 massacre in Newtown, Connecticut that killed 26, legislators have had great difficulty enacting more restrictive laws.

Similarly, deaths and serious injuries caused by reckless or distracted drivers who are not drunk have also proven hard to legislate. In New York State, current laws permit criminal prosecution only if the driver has previous driving offenses or committed a second violation at the time of the crash. Efforts to strengthen these laws have generated traditional arguments: such deaths are unintentional “accidents.” It is wrong to prosecute drivers for being careless if they are not malicious; and, most notably, a certain number of deaths are the “price one pays” for running a busy, congested city like New York.

Given my background in public health research, I am very familiar with these types of warnings about limiting public health powers. But as someone who has now personally experienced a tragic, unnecessary death, I worry that the banner of libertarianism too often drowns out rational, middle-of-the road approaches to genuine harms. It is hard to imagine anyone who has lost a relative or dear friend in such a manner to see such innocent deaths as the price of doing business. Indeed, it is downright chilling to suggest this. When cries for preserving our rights drown out the cries of grieving parents and children, something has gone very wrong.

Working closely with legislators and other activists, my sister was able to get New York’s City Council to pass “Cooper’s Law,” which mandates that the local Traffic and Limousine Commission suspend the license of a taxi driver who has killed or seriously maimed a pedestrian and do a formal investigation. There was initially typical reflexive opposition to this law on libertarian grounds but, thankfully, saner heads prevailed.

Similarly, let’s listen very closely to an initiative that is getting a lot of attention in the wake of the Santa Barbara deaths: gun violence restraining orders. What this would do would be to enable a judge — in response to the concerns of family members or therapists — to issue an order preventing someone with mental illness from purchasing firearms and permitting the seizure of firearms already in his or her possession.

In the face of such a litany of tragic deaths, how can this proposal be seen as anything but reasonable? Among the foremost liberties Americans deserve is the right to sensible laws that protect us from experiencing the same needless tragedies over and over.

This was originally published in the Huffington Post on June 12, 2014.