A new biography tells the story of one of the most influential doctors of the past century, and his evolution as an artist.

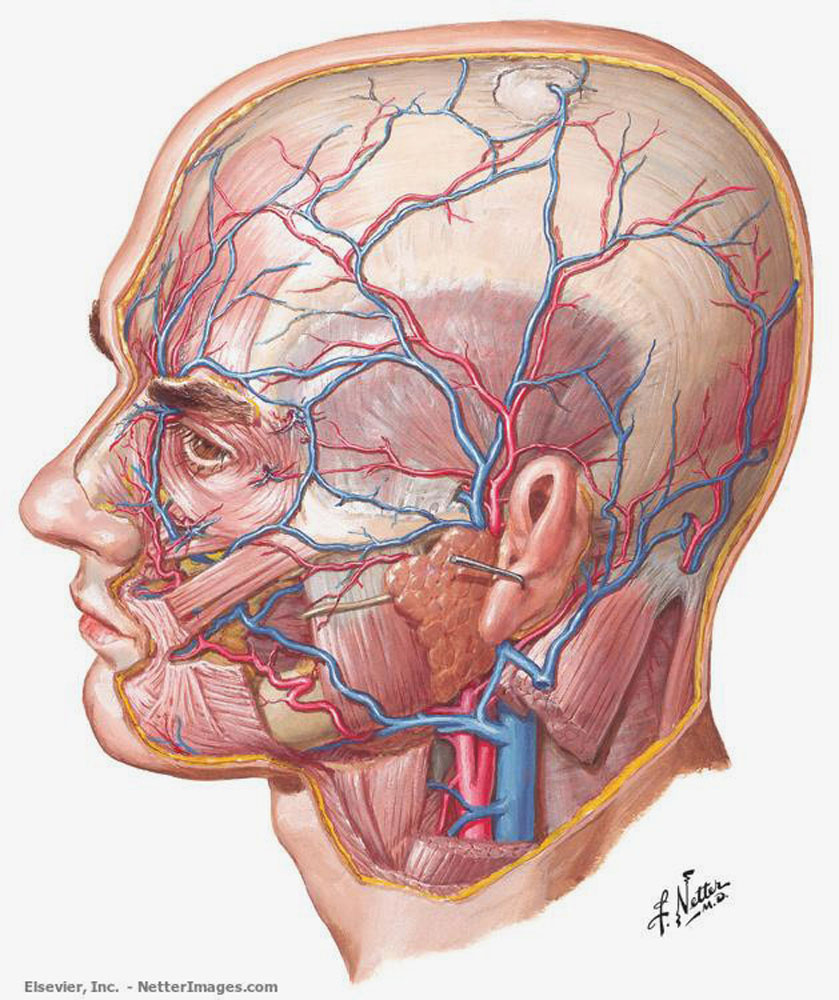

To generations of medical students, from mine to the present, the name Frank Netter has a magical connotation. He was the doctor who drew the remarkably lifelike images that we all used to learn anatomy. They were so lifelike, we joked, that we trusted them more than what we actually saw in our cadavers or on CAT scans.

Who was Frank Netter and how did he come to be the world’s most famous medical illustrator? Fortunately, his daughter Francine has written a forthcoming biography of her father, entitled Medicine’s Michaelangelo.

As we learn, if Netter’s mother had had her way, Netter would have retired his paintbrush in favor of a stethoscope. It is because he did not, though, that we have timeless illustrations like this.

Netter was born in Manhattan in 1906 and showed aptitude for art at an early age. During high school, he studied at the prestigious National Academy of Design, where he drew nude figures. At New York’s City College, Netter drew portraits and cartoons for the school’s yearbook and spent the summers as an artist and set designer at a hotel in the Catskills.

But despite his remarkable talent, he had promised his mother he would go to medical school and, in 1927, he enrolled at New York University Medical College. While his fellow classmates spent their spare time studying for examinations, Netter drew haunting images of Bellevue Hospital, where he would eventually complete his internship and, in a harbinger of things to come, a picture entitled “Healing Hands,” in which a doctor applied a bandage to a patient’s fingers.

Netter did practice medicine briefly but, as Francine writes, “the demand for Frank’s sable brush grew faster than the demand for his scalpel.” His portraits, drawings of body parts and, at the behest of pharmaceutical companies, images of new drugs and how they worked were simply too vivid and unique to ignore. In 1934, Netter saw his last patient.

It would be Netter’s relationship with drug manufacturers that propelled forth his career as a medical artist. In 1937, the Ciba Company asked him to prepare an illustrated flyer for its version of digitalis, a heart drug. A remarkably long marriage was born. Over the next five decades, Netter worked with the company, later known as Ciba-Geigy, to produce the Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations and the Clinical Symposia, beautifully illustrated books that depicted both normal anatomy as well as the pathology associated with specific diseases. The over 4,000 illustrations made by Netter during his career also depicted patients (drawn from models) suffering from conditions like bronchial asthma, angina and major depression. One picture showed a patient with end-stage liver disease on water restriction desperately drinking from a toilet. When Netter required surgery for an aortic aneurysm near the end of his life, he used the occasion to make diagrams of the operation he needed. Netter’s work was voluminous, covering a vast array of topics and diseases. Ciba distributed his illustrations far and wide to medical students and physicians—usually for free—as a marketing tool.

Words do not really do justice to the exquisite nature of Netter’s diagrams. The Saturday Evening Post termed him the “Michelangelo of Medicine” and featured his work alongside that of Norman Rockwell. A reviewer of Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, which compiled hundreds of Netter’s best images, equated Netter’s influence on anatomy to that of Leonardo Da Vinci.

Medicine’s Michelangelo is less of a page turner than a labor of love. If many famous artists are temperamental, Netter was not. Indeed, he seems to have been humble to a fault. In addition, the book contains lots of names of Netter’s various coworkers that will not be of interest to the average reader.

Nor did Francine Netter situate her father’s career within other relevant developments in the history of medicine. For example, it would have been interesting to explore Ciba’s decision to distribute Netter’s work for free to physicians in light of all of the negative commentary about the marketing techniques of modern pharmaceutical companies. And I would have loved to have heard what Frank Netter thought about the revelations that the famous German atlas of human anatomy by Eduard Pernkopf contained images of Jews killed during the Nazi regime.

But Francine Netter has done an admirable job of documenting her father’s remarkable career. As one of Netter’s many awestruck colleagues wrote, “I do not know of anybody in the past several hundred years who has done anything like this.”

Originally published in theatlantic.com, September 17, 2013