Mental illness remains highly stigmatized, even after celebrities like Brooke Shields, Mel Gibson and Robin Williams went public with their stories. So it was really a big deal 60 years ago when the Boston Red Sox outfielder Jimmy Piersall wrote two articles in the Saturday Evening Post entitled “They Called Me Crazy—And I Was.” Mr. Piersall’s courageous description of his struggles with manic depression, now called bipolar disorder, helped bring the disease and its treatments out of the shadows.

That Mr. Piersall had mental illness was at first far from clear. He was born in 1929 to a mother who would later spend time in mental institutions. As a child, he had always been high strung and, as a slick-fielding minor league centerfielder in the Red Sox organization in the early 1950s, seemed incapable of relaxation.

But during the winter prior to spring training in 1952, Mr. Piersall truly began acting strangely. Concerned that the Red Sox wanted to make him a shortstop and nervous about becoming a father for the first time, he went to movies and roamed the streets without his wife, Mary. He had to be forced to go to spring training.

Mr. Piersall made the Red Sox, but his troubles continued. He got into fights with teammates and opposing players, did calisthenics and dances in the outfield and clowned with fans during games. Frustrated, the Red Sox sent him to their minor league affiliate, the Birmingham Barons, but Mr. Piersall got worse, heckling umpires, climbing into the stands and once even running around wearing only an athletic supporter.

Finally, in July, the Red Sox had had enough. They forced Mr. Piersall to have a psychiatric evaluation, which eventually landed him at Massachusetts’s Westborough State Hospital, where he was diagnosed with manic depression.

Remarkably, from our modern perspective, there were many people who questioned the hospitalization. Some sportswriters thought Mr. Piersall’s antics were just an act, terming him “impish” and “zany,”; the press described his condition as “mental exhaustion” or a “nervous breakdown.” “We just thought he was nuts,” teammate Fred Hatfield later remarked.

That Mr. Piersall’s condition was serious was confirmed by the treatment he received: electroshock therapy. (It’s now termed electroconvulsive therapy.) The shock treatments, plus psychotherapy, proved remarkably successful in stabilizing his mood swings. In April 1953, Mr. Piersall was back as the Red Sox’s starting right fielder.

Certainly he did not have to tell his story. Yet he did, first on a 1954 Chicago television show. “I pointed out the need for coming into the open,” he remarked at the time, “and letting the world know that there were thousands like me, who would be cured if people tried to understand them.”

Then, in early 1955, working with a Boston sportswriter named Al Hirshberg, Mr. Piersall published his two-part series in the Saturday Evening Post, a popular national magazine. He was extremely candid, describing in detail his shock therapy, a treatment that most Americans viewed as barbaric. The articles were a prelude to a book, “Fear Strikes Out,” published in May of 1955, and eventually a 1957 Hollywood movie of the same name, starting Anthony Perkins as Mr. Piersall.

The public response to the book and film was highly positive. “His case is more than substantial proof,” wrote a Boston journalist, “that mental illness, so frightening to so many people, can be cured.”

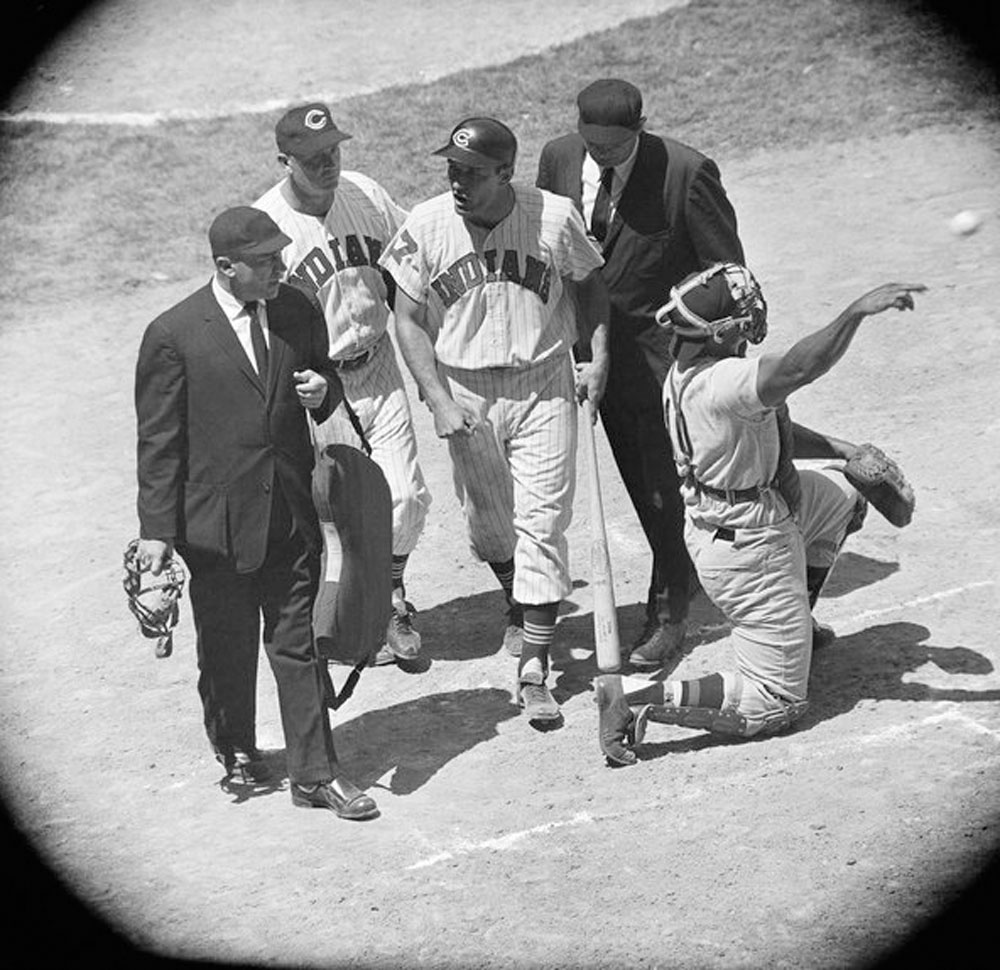

Yet Mr. Piersall’s story, while undoubtedly inspiring, proved more complicated. For one thing, most people with severe mental illness rarely are completely cured and Mr. Piersall was no exception. When playing for the Cleveland Indians in 1960, he experienced a return of his manic symptoms, once again picking fights, using bug spray in the outfield and leaving games before they were over. He again saw a psychiatrist, but managed to remain out of the hospital. Some opposing fans and players used Mr. Piersall’s mental illness as a way to ridicule him, calling him terms like “goony bird” and “cuckoo.”

Despite his manic depression, Mr. Piersall played major league baseball for 16 years, retiring in 1967. He subsequently worked in a series of baseball jobs, including as a sportscaster for the Chicago White Sox, where his outlandish statements often landed him in hot water. In 1974, he began to take lithium, a common medication used for manic depression, which he admitted modified his extremes.

Over the years, Mr. Piersall started to downplay the psychiatric causes of his behaviors. In 1976, he termed psychiatry not an “answer” but a “crutch.” In a 2001 ESPN documentary, he said psychiatrists “talk too much” and “do nothing.” He even remarked that mental illness could best be treated by self-help. “You can cure it, or you can lick it,” he told ESPN, “if you want to.”

If many of Mr. Piersall’s later remarks minimized the seriousness of mental illness, echoing our ongoing cultural ambivalence about how “real” it is, his initial choice to go public did a world of good for people who had long suffered in silence. As one fan with mental illness told him in 1954, he was a “source of inspiration.”

Originally published in the “Well” blog of the New York Times on April 9, 2015