In the years after World War II, Eleanor Roosevelt routinely won polls as America’s most admired woman. But in a 1952 Gallup poll, she was beaten by an Australian nurse, Elizabeth Kenny, popularly known as Sister Kenny.

Today, Elizabeth Kenny is largely forgotten. But thanks to a new biography by the Yale University historian of medicine Naomi Rogers, “Polio Wars: Sister Kenny and the Golden Age of American Medicine,” readers can learn why she gained such fame. And while Ms. Kenny’s work was mostly in polio, which has now nearly been eradicated, her emphasis on the care of individual patients and close bedside observation could not be more relevant in an era dominated by randomized controlled trials.

Ms. Kenny was an unlikely celebrity. Born in Australia in 1880, she became a “bush nurse,” serving a largely rural population. It was World War I that opened up her vistas; she worked as a British army nurse on troop ships and earned the honorific title “Sister,” the equivalent of a lieutenant, for her service. Contrary to popular belief, Ms. Kenny was not a nun.

Meanwhile, in Australia and around the world, rates of polio were on the rise in the 1920s and ’30s. Although only one in 200 cases damaged nerves in the spinal cord, polio, a viral disease, was dreaded. Most of its victims were children and young adults. Those severely affected first developed fever and body aches, which progressed to varying degrees of paralysis in hours to days. The most advanced cases affected the brain stem and respiratory muscles; these patients required iron lungs, an early version of the respirator, to breathe. Five to 10 percent of paralyzed polio patients died; up to half had persistent partial paralysis.

Ms. Kenny had encountered patients with polio before the war and made a crucial observation: heated wool cloths and muscle exercises seemed to relieve patients’ pain and contractures, or muscle shortening, which she thought resulted from muscle spasm in addition to nerve damage. Plus, Ms. Kenny believed that patients needed to play an active role in their recovery, learning the names of affected muscles and how they worked. These interventions flew in the face of traditional polio treatment, which emphasized using splints to immobilize paralyzed limbs. Doctors believed that rest protected the damaged limbs and that persistent contractures could be treated by surgery.

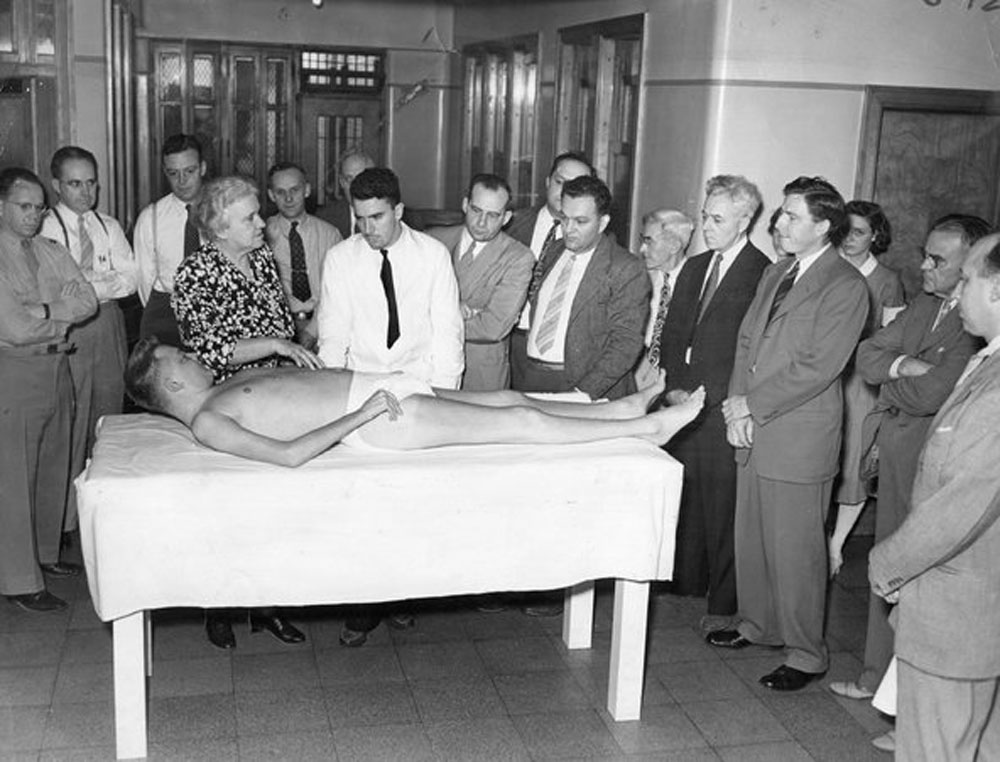

Ms. Kenny’s apparent successes led her to travel throughout Australia and England to demonstrate her technique. But it was in the United States where she achieved her greatest fame and lived out most of her life. Based in Minneapolis, she opened the Elizabeth Kenny Clinic to treat polio patients from across the country. A 1946 Hollywood movie, “Sister Kenny,” starred Rosalind Russell.

Ms. Kenny attracted passionate support from patients and families who believed that her ministrations had restored their strength and mobility. In her 1943 autobiography, “And They Shall Walk,” Ms. Kenny quoted one of her young patients as saying: “I want them rags that wells my legs.” The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, later known as The March of Dimes, provided financial support for her efforts.

But Ms. Kenny was criticized as well. Physicians and physical therapists who relied on immobilization believed there was no scientific basis for her therapy. They pointed to other claims made by Ms. Kenny, notably that massaged muscles might send out nerve fibers to help heal more severely damaged muscles, as evidence that she did not understand the physiology of the disease. These critics called for randomized clinical trials — which were never done — to ascertain whether or not Ms. Kenny’s system had value.

As Dr. Rogers shows, Ms. Kenny irked the American Medical Association and the rest of the medical establishment for reasons beyond her medical theories. First, she was a nurse questioning the authority of physicians. Second, she was a woman — and a very outspoken one fond of dramatic hats and corsages — challenging the overwhelmingly male medical profession. Third, as Dr. Rogers admits, Ms. Kenny was prone to embellish both her own story and those of her patients.

But it is Ms. Kenny’s fierce adherence to what she observed at the bedside that holds the most relevance today. She thought that she could see and feel muscles improve as she ministered to her patients. She saw her patients recover at rates that — she believed — were much higher than those treated conservatively. Who needed clinical trials when the proof was right in front of her face? According to Ms. Kenny, Dr. Rogers writes, “the empirical evidence embodied in her patients’ recovery proved her therapy worked.”

Was Ms. Kenny correct? Yes and no. Her emphasis on early mobilization has come to be a mainstay of not only polio treatment but of physical therapy more broadly. Yet some of her claims about the nature of the disease and how patients recovered proved wrong. The successful development of a polio vaccine in the 1950s made these debates much less pressing.

But perhaps Ms. Kenny’s greatest legacy, in an era of evidence-based medicine and reliance on large-scale clinical trials involving thousands of patients, is that keen clinical observation — what the physician-writer Dr. Abraham Verghese has termed “bedside medicine”— still has its place. Her opponents, Ms. Kenny once wrote, “have eyes but they see not.”

Barron H. Lerner, a professor of medicine and population health at New York University School of Medicine, is the author of five books, including the forthcoming “The Good Doctor: A Father, A Son and the Evolution of Medical Ethics.”

Originally published in The New York Times (The Well Blog) December 26, 2013